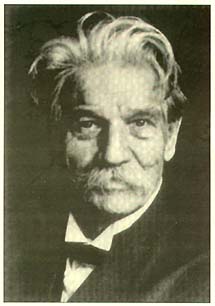

| Albert Schweitzer's address given at the Goethe Bicentennial Convocation and Music Festival, Aspen, Colorado, July 6 and 8, 1949. On the 6th it was given in French, translated by Dr. Emory Ross. On the 8th it was given in German, translated by playwright Thornton Wilder. Goethe: His Personality and His Work by Albert Schweitzer We have gathered here to commemorate the two hundredth anniversary of the birth of Goethe. Let us devote this hour to a review of his life, his work, and his though, and consider together the message he brings us. When Goethe died, he was famous but not popular. His compatriots had little understanding of his work. Abroad he was admired in certain quarters as the author of Werther and Faust, but his work as a whole was not appreciated. As for the Goethe cult in Frankfort, it is significant that the centenary of his birth, which would have been celebrated just a few years after his death, was not observed in this city where he was born. The mass of the people, animated by the revolutionary sentiments of 1848, were not inclined to pay homage to a man they despised for having been the servant of a prince. He himself had been compelled to admit that none of the books that followed Götz von Berlichingen and Werther had had any real success, and this fact made him aware that they were not popular. To Eckermann, the loyal assistant who had worked with him since 1823, he even expressed the conviction that they could never become so. But in this he was wrong. They have become popular: as time has passed, they have found their way into the hearts of men. More and more, Goethe has come to have a choice place among the poets, not only in his own land but everywhere. How can this be explained? This great poet is at the same time a great master in the natural sciences, a great thinker, and a great man. All together, these qualities constitute his significance and bring him to public attention as a personality of a very special kind. So it happens that, in this year 1949, the bicentenary of his birth is being celebrated throughout the world, while the centenary of it did not stir even his native city. Goethe the Poet In what does the peculiar charm of his creative writing consist? Let us consider first of all the language he uses. Goethe is a visionary. He expresses himself in images -- an attitude that, even in his youth, he recognizes as natural to him. He knows the secret of word-painting. We see what he sees and wants us to see with him. Another peculiarity is that he expresses himself, not in sonorous, rhetorical language, glistening with an abundance of adjectives, but in simple, sober, every day language, which he knows how to lift into the realm of poetry. Characteristic also is the rhythm of his poems. The rhythm of his phrasing is not usually made to coincide with his poetic meter. There is, indeed, tension between them. In this there is a kind of affinity between Goethe and Bach, whose themes are not married to the natural rhythm and the accents of the measure employed but have their own rhythm and their own accents. In the case of Goethe, the independence of these two rhythms -- that of the phrasing and that of the meter -- produces the impression, when the verses are read or spoken, of a kind of solemn prose, which is at the same time simple and elevated. As for the subject matter, the distinction and charm of his work reside in the fact that the subjects are borrowed from his own life and from the thoughts which are natural to him. From his youth on, he is aware of their completely personal character. He does not hesitate to say that he considers his books fragments of a confession. Unlike Schiller and others, he cannot just choose a subject arbitrarily and then develop it by entering into it and making it appear significant. When he happens to produce something that way, he is out of his element, like a swan emerging from the water to waddle on the land. The books he fashions in that manner -- Clavigo, Stella, and Grosskophta, the Citizen General, and others, as well as his texts for operettas and operas -- show so little trace of his spirit that they hardly seem authentic, even though they are signed by him. Let us consider his attitude in regard to the Faust theme. In this case, the material was already fixed in existing narratives. For sixty years, Goethe tries desperately to utilize this material. It appeals to him, for he finds himself there as nowhere else. He is Faust; and he is also Mephistopheles, on whom he can project some of the ideas active in his own mind. None the less, the subject presents almost insurmountable difficulties, in that it has already been firmly shaped by tradition. Compelled to adhere to this tradition, Goethe must include Faust's love for the fateful Helen, who is recalled from the realm of the dead by the power of Mephistopheles. For the same reason, he must have Faust appear at the emperor's court and, with the help of Mephistopheles, arrange the spectacles to be presented there. At the same time, in order to find his own real self in the traditional Faust, he must violate the material by incorporating into it the Gretchen episode, which is wholly foreign to it. Faust must actually become guilty by harming a trusting child. Yet, though he is guilty, he must be saved and not damned -- another violation of the established tradition, according to which Faust goes to hell. Goethe must implicate Faust in this way, because he himself is guilty in his mistreatment of Friederike Brion de Sesenheim and is convinced that he has found forgiveness. All of these difficulties make it impossible for him to finish the work, begun in his youth, until a little while before his death. Yet they have somehow to be faced and surmounted so that he may find himself again in Faust -- so that he can make this drama also a confessional fragment. Goethe the Master of Natural Science Goethe has an innate leaning toward the natural sciences. As a student at Leipzig and Strasbourg he seeks out the society of those who are devoting themselves to this field, and at Strasbourg he begins to show an interest in anatomy. His first discovery is made in the field of comparative anatomy. In that day it was established that the intermaxillary bone, which is located between the bones of the maxilla, and unites them, is found in animals, including monkeys, but not at all in man. It pleases men to find this distinguishing feature between their structure and that of the other vertebrates, but Goethe cannot get accustomed to the idea that nature intended to set man apart in such a shabby way. He begins to study the matter, and his research teaches him that man does have a rudimentary form of the intermaxillary bone, fused with the adjacent parts of his facial structure. In 1786 Goethe makes his discovery public. Little by little, the anatomists are obliged to recognize the validity of his assertion. His administrative activities include a responsibility for agriculture, which first leads him to become adept in practical matters of botany. He begins to acquire scientific competence in this field also, and is fascinated by the problem of the variations in structure of different plants. In 1788, in Sicily, he solves the problem with the theory that all plant organs have their common origin in the leaf and are only transformations of it. In 1789 he publishes this discovery. Now it is the botanists who are compelled, in the course of time, to bow to the poet who is delving in natural sciences. In 1790 he resorts to the principle of transformation to explain the shape of the skull, hypothesizing that it is formed by the evolution of the cervical vertebrae. Several years later the anatomists themselves set forth this theory, but credit for the discovery must go to Goethe. In later years he spends a great deal of time and energy studying the evolution of the vertebrate skeleton. The poem entitled "Metamorphosis of Animals," which appears in 1819, contains his major conclusions. In his ripe old age it gives him satisfaction to have the great French zoologist, Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (1772-1844) cite him before the French Academy as a pioneer in the field of evolutionary theory. The occasion is Saint-Hilaire's defense of this theory against Cuvier (1769-1832), the founder of comparative anatomy. Practical reasons lead him to a scientific interest in mineralogy and geology, as they did in botany. In 1777 he is asked to make exploratory studies before reopening and managing the Ilmenau mines, which had produced copper and silver until water entered the workings and put an end of the operations. He attacks the task with enthusiasm. In the course of research pursued over a number of years, it becomes clear to him that the formation of the crust of the earth is primarily due to a slow evolution, with volcanic activity a secondary cause. He is also the first to express the opinion that erratic boulders have been deposited by the glaciers which formerly covered Europe, and that moraines are likewise the work of glaciers. Again, practical reasons lead him to seek an explanation for the phenomenon of color. He discusses, with the painters who frequented Rome, the methods used to get color effects in painting. These discussions lead him to make studies and to take issue with the theory published by Isaac Newton in 1704: that white light is composed of different colored rays and that a straight beam of white light passing through a prism would break up into these rays. Goethe opposes this theory with his own: that colors are not a property of diverse rays, but are phenomena caused by the meeting of light and darkness, white and black. A predominance of light produces yellow; of darkness, blue. The two together produce green. Red is found between the blue and yellow, of which it is only a modification. From 1791 until his death, Goethe battles for his color theory in a number of publications, basing his arguments on a series of observations and experiments. He devotes much more time and effort to these experiments and publications than he does to all of his poetry and prose put together. But these sacrifices of time and trouble are all in vain. The studies of Fresnel, Maxwell, and Lorentz on the nature of light confirm Newton's theory. Although Goethe does not win his case -- and could not win it -- his labors have had an important influence upon the study of color and optics. His observations and experiments have propounded problems for Newton's theory, problems which it has not always been able to solve in a satisfactory manner. Therefore, new investigators are constantly appearing to take his side against Newton. It is interesting to note that the theory of homogeneity of colors, which has appeared in painting, has much in common with Goethe's color theory. Goethe represents a natural science which has the distinguishing feature of being based exclusively on direct observation. Although he cannot ignore the service rendered by the microscope and the telescope, he does not favor the use of research apparatus. The man who knows how to make good use of his senses is, for Goethe, the greatest and most precise instrument of observation imaginable. In utilizing instruments, he thinks, we torture nature in order to extort confessions from her, instead of leading her gently to reveal her secrets. But it is not only instruments of precision that Goethe dislikes; it is mathematics also. Mathematics must only be used when we are dealing with mechanical problems. When mathematics presumes to explain other phenomena of nature, it can only render us a very dubious service. In reality mathematics, as we know very well today, has been called upon to play an increasingly important role in the natural sciences. It could not have been otherwise. How does it happen that Goethe wishes to cultivate the natural sciences in a way that is already outmoded in his own age? In part, this is because he lacks an aptitude for mathematics and for the long-continued discipline it demands. Since instruments of observation require arithmetical calculations, they are likewise alien to him. Moreover, Goethe is convinced that true understanding of nature can come only from the most personal activity of the human mind, never from something impersonal. For him an insight into the essence of nature must begin with direct observation; man's own inner being is the instrument by which the essence of nature can be understood. In his writings Goethe frequently expresses this view of his about the understanding of nature. He describes it most clearly at the close of his 1819 poem about comparative osteology: Freu dich, höchstes Geschöpf der Natur; Du fühlst dich fähig, Ihr den höchsten Gedanken, Zu dem sie erschaffend sich aufschwang, Nachzudenken. Rejoice, thou masterpiece of nature; Thou dost feel able To repeat after nature The highest of thoughts to which she soared Creatively. In his Theory of Colors he writes: Wär' nicht das Auge sonnenhaft, Die Sonne könnt' es nie erblicken; Läg' nicht in uns des Gottes eigne Kraft, Wie könnt' uns Göttliches entzücken? Did not the light shine in the eye, How could the sun at all excite us; If God's own strength did not within us lie, How could the things divine delight us? Spiritual insight must accompany physical awareness if we are to have strong understanding. So Goethe dares to say, "If we do not see with the eyes of the spirit, we grope blindly about everywhere, but more particularly in the investigations of nature." Only that fundamental appreciation of nature that can be won through man's natural capacity for observation has meaning for Goethe. By this means, man comes into his proper spiritual relationship with nature, and from this relationship he gains comprehension of and guidance for his own life. For this reason, Goethe champions the natural science that can become the personal possession of any man endowed with a gift for sound thought and reflection. For this reason, he dares to condemn laboratory instruments and mathematics at a time when this is no longer permissible in the realm of natural science. How great, nevertheless, is Goethe, the student of nature, even in his conservatism! It is as if natural science wanted to demonstrate once again through him what it was capable of accomplishing by the simplest of means. Staying within these limitations and using his magnificent gift for observation, Goethe leads botany and anatomy, as well as mineralogy and geology, along the way to the most modern methods of research. Hardly ever has history in any field of knowledge or skill offered such a paradoxical unity of reaction and progress. Goethe the Thinker What conception of the world and of life does Goethe come to hold? To what system of philosophy does he belong? There are two kinds of philosophy: the dogmatic and the nondogmatic. Dogmatic philosophy does not start from the observation of nature; rather, it applies philosophic conceptions to nature and interprets it accordingly. This type of philosophy is speculative and sets about constructing systems. Nondogmatic philosophy starts from nature, attaches itself to nature, and tries to interpret it according to observations and experiments which are being constantly enlarged and deepened. This is natural philosophy. These two thought currents run parallel to each other in the history of the mind. In ancient days, systematic (dogmatic) philosophy is represented by Plato and Aristotle. In modern times, it reaches it apogee at the beginning of the nineteenth century -- in Fichte, Schelling, Hegel, and Schopenhauer, who are all contemporaries of Goethe. Natural (nondogmatic) philsoophy is born in Ionia in the Greek world of Asia Minor. It begins with Thales, Anaximander, Heraclitus, and Empedocles, who try to find the origin of life in matter and its evolution. Later Epicureanism and Stoicism, which also try to stick closely to nature, have the character of natural philosophies. During the Renaissance, with a new blossoming of the natural sciences, efforts are made to revive the philosophy of nature. The most remarkable is that of Giordano Bruno. The Renaissance and the post-Renaissance era, however, are unable to create a well elaborated and convincing natural philosophy. Spinoza succeeds in reviving the spirit of the Stoic philosophy of nature, but he is compelled to attribute to it the language and the formulas of Descartes. The young Goethe is influenced by Giordano Bruno and Spinoza. As a thinker devoting himself to the natural sciences, he becomes the representative of natural philosophy at a time when the great systems of Fichte, Schelling, and Hegel are the vogue and claim to be complete and definitive systems. He could not have chosen a worse time. Fine, modest man that he is, he begins to study the current philosophy, certain that it can teach him something. He feels it his duty to apply himself to the reading of Kant; he sits at the feet of Schiller, Kant's prophet, and permits himself to be catechized by the latter on his celebrated theory of knowledge. He knows Fichte, Schelling, and Hegel personally. All three of them have been invited, through his influence, to the University of Jena. (Fichte is active there from 1794 to 1799, Schelling from 1798 to 1803, Hegel from 1801 to 1806.) He tells us in his journal about allowing himself to be initiated by Schelling in his pseudo-philosophy of nature, which Goethe tries to appreciate. Finally, however, he is compelled to confess that the way of thinking common to Kant, Fichte, Schelling, and Hegel, as well as to Schopenhauer, is foreign to him. He does not know what to make of it, precisely because it does not start with the study of nature but applies prefabricated theories to it. In the aphorisms of his old age he says, "I have always been on my guard against philosophy. My point of view has always been based on common sense." This dictum is supplemented by another: "We have for a long time been concerned with the critique of reason; I should like to see a critique of human understanding. It would be a real benefit to the human race, if we could show convincingly how far common sense can go, and that is exactly far enough to satisfy completely the needs of our earthy life." Goethe's work, therefore, is concerned with the philosophy of a genuine and profoundly healthy human understanding. How can an individual by himself and by his own research arrive at convictions capable of guiding him on the right road throughout his life? This is the important thing to Goethe. He believes that he cannot reach simple and wholesome convictions except by starting from reality, from the knowledge which he gains by observing nature and himself. To be realistic in order to achieve a true spirituality: this is Goethe's watchword. The fundamental idea to which one must come is that in nature there are both matter and spirit, the two together. The spirit operates on matter as an organizing and perfecting power. The spirit leads us out of chaos, away from the primitive. It is manifest in the evolution which is taking place and which we ourselves have noticed in nature. When we observe nature within ourselves, using the eyes of the spirit, we are aware that here also there are both matter and spirit. As we study the phenomena of the spirit within ourselves, we find that we belong to the world of the spirit and should let ourselves be guided by it. Goethe's whole philosophy is based on the observation of material and spiritual phenomena within and without ourselves, and in the conclusions to be drawn therefrom. The spirit is light struggling with matter, which in itself represents darkness. Everything that takes place in the world and in ourselves is the result of this conflict. If Goethe clings so firmly to his theory of colors, it is because his interpretation of colors as phenomena associated with the meeting of light and darkness is in accord with his conception of what is taking place in nature. This perception of a genuine and profoundly healthy human understanding derived from the philosophy of nature seems very modest when compared with the perfect knowledge claimed by the great systems. It must resign itself to being always incomplete, because we have only a very imperfect knowledge of nature at our disposal. But such as it is, it is true. And truth for Goethe is the greatest of all values. "Truth is wisdom," he asserts. He believes he may risk one affirmation, based on his own experience with the simple philosophy of nature: that this knowledge, however incomplete, is sufficient to conduct us through life. In his opinion, anyone who follows the simple way of thought that he has pointed out will arrive at all those worthwhile ethical and religious convictions that have ever appeared in the spiritual history of man, and will come to possess them in their original and purest forms. What are the elements of the idea of the world and of life to which natural philosophy leads us? In the first place, Goethe admits that certain elemental and obscure forces, seeking to manifest themselves in their own way, are at work in nature as well as in ourselves. He calls them "daemonic" forces. These daemonic forces of nature he represents in "Walpurgis Night" and incarnates in Mephistopheles. In history they are manifest in certain men. Such men, according to the description he gives in Poetry and Truth do not always excel by their spirit or by their talents; they are rarely remarkable for their goodness. But a prodigious force emanates from them, and all moral forces together are powerless against them. Thus they attract the masses. Goethe finds fault with Kant for not taking into account the existence of the daemonic. "The Kantian imperative," he writes," automatically and autocratically assumes [a world of] men in whom passion hardly ever breaks forth and still less is dominant. But we often see men in the grip of invisible forces which they are unable to resist, which determine the course they take, and often seem to control arbitrarily their inclinations and their activities in a realm lying above all law." The daemonic, however, is not necessarily evil in its activities. In certain circumstances it can be active for good. "Great and primitive forces," he says, "eternally present or originating in time, work unceasingly, whether for good or evil is accidental." In all fateful events, whether small or large, Goethe imagines a manifestation of the daemonic, sometimes in good ways, sometimes in bad. "In my acquaintance with Schiller," he once remarks to Eckermann, "there was always something of the daemonic at work." In a conversation with Eckermann in 1831 concerning the new edition of his book Metamorphosis of Plants, he says, "The book meanwhile is causing me more trouble than I anticipated; it is even true that at the beginning I embarked upon this task almost against my will, but something daemonic dominated me in it, something which could not be resisted." As he confided to his faithful helper: "Certain forces had been released by the delays in completing the new edition of the book, which made it possible to finish the work, though this would not have been conceivable the year before. . . . This sort of thing has often happened to me in my lifetime, and in such circumstances one comes to believe in a higher influence, in something daemonic, that one worships without pretending to explain it further." So we encounter in him again and again the idea of daemonic power. This fundamentally natural element, which man bears in himself from birth, is his fate. He cannot get rid of it. "We cannot separate ourselves from that which belongs to us," says Goethe in Maxims and Reflections. Goethe's idea of the daemonic in man differs from that of Socrates. With the latter, the daemonic dwelling in man is a supernatural, spiritual being differing from himself -- a being that suggests to him what he must think and how he must act. With Goethe, it is the cosmic, untamed forces of nature striving against the influence of the spirit, which is also present in man. The idea of the daemonic, which he derives from his natural philosophy, carries with it traces of the Christian conception in which it is something opposed to the divine. Goethe wrestles, as all of us must, with the problem of destiny and liberty. His most bitter work, Elective Affinities, sets before us two women and two men whose existence is fatally determined by a love which they should fight but do have the power to oppose. Goethe generally holds to the conviction that we can often master our destiny by the attitude we adopt in the face of events. A man should try to hold his ground in dealing with the daemonic. In an interview with Eckermann on March 18, 1831, Goethe says we are in the position of those who play a game which the French call ombre, where a great deal is decided by the dice which are thrown, but where it is left to the skill of the player to place the men well on the board. In the same way, the painful events of our life have a meaning for our internal evolution. Goethe believes that the difficult in our life, whatever its origin, is absolutely necessary for our inner progress. In Wilhelm Meister he has the harpist sing: Wer nie sein Brot mit Tränen ass, Wer nie dei kummervollen Nächte Auf seinem Bette weinend sass, Der kennt euch nicht, ihr himmlischen Mächte. He who with tears ne'er ate his bread, He who through dark and saddened hours Sat never weeping on his bed, He knows you not, you heavenly powers. Submitting to the spirit, man must strive for true humanity, so that he may become whatever his nature destines him to be. The two basic ideals in a profoundly human attitude are purity and goodness. The ideal of purity takes shape in Goethe during his inner conflict in the first Weimar period. Purity, to him, means that a man rids himself of hypocrisy, subterfuge, falsehood, and anger, and becomes a true and simple being. This ideal is proclaimed in Iphigenia and in Tasso. Iphigenia cannot decide to employ perfidy and falsehood, as necessity seems to command, in order to save herself, her brother, and her brother's friend. She has the courage to remain truthful; by her sincerity she impresses the barbarian king, who decides to let them go in peace. Through truthfulness she remains a pure priestess and is able to atone for her murder-profaned parental home. This drama is one of Goethe's most powerful and engrossing poems, which generation after generation will read with fresh emotion. Tasso, the great poet, lacks the strength to master himself. This lack brings misfortune upon himself and suffering on those he loves. The supreme manifestation of the spirit in man is love. The spirit does not permit man to be satisfied with simply asserting himself and imposing his will on other beings, it compels him to be considerate of them. In this way the spirit brings order out of the chaos of human relations. Without kindness man is not man in the full sense of the word. The man who truly understands himself cannot do otherwise than let himself be guided by love. He does not find love in nature. Love is the divine spark within him. So the hymn in which Goethe exalts the truly human attitude is called "The Divine." He begins it in this way: Edel sei der Mensch Hilfreich und gut! Denn das allein Unterscheider ihn Von allen Wesen Die wir kennen. Noble let man be, Helpful and good! For that alone Sets him quite apart From every being Which we can know. Heil den unbekannten Höhern Wesen, Die wir ahnen! Ihnen gleiche der Mensch; Sein Beispiel lehr' uns Jene glauben. Hail to all the unknown Higher beings, Which we surmise! Man should imitate them; His life should teach us To accept them. Goethe says also of love: Lieb' und Leidenschaft können verfliegen, Wohlwollen aber wird ewig siegen. Love and passion may fly away ever, But kindness of heart will lose the day never. Wenn ein Wunder in der Welt geschieht, Geschieht's durch liebevolle, reine Herzen. When a marvel happens in the world, It comes through innocent and loving spirits. "In the face of another's great superiority," he says, "there is no remedy but love." And again: "There is a politeness of the heart. It is akin to love." A curious fact to be noted is this: Goethe pays no attention to the first manifestation of moral feelings among beings inferior to man, feelings which are revealed in the devotion with which they take care of their offspring. He concerns himself only with their anatomical development, not with their spirit. We observe that Goethe's ethics does not encourage enthusiasm like that, for instance, aroused by the ethics of his English contemporary, Jeremy Bentham (who was his elder by several weeks and died in the same year he did). Bentham urges man to make ceaseless efforts to achieve the greatest possible happiness for the greatest possible number. Goethe does not consider this thoroughly utilitarian principle, as fundamental to ethics, any more than he admits the categorical imperative of Kant. He does not want the individual to feel compelled to bring his life into the kind of harmony with the supreme good of the community that Bentham demands. Accordingly, Goethe treats Bentham like an "old fool." His principle is: "Do good for the sheer love of goodness." For each one of us, he argues, destiny reserves an ethical activity which conforms to his particular character and to the circumstances of his life. Each of us must recognize the fact that he is by nature deposed to goodness. Through this individual practice of goodness by a great number of people, the welfare of society will be realized more naturally and more completely than by a procedure that would make everybody the slave of a single, identical utilitarian principle. Each of us has his particular task to fulfill in the world. The course of his life and his reflection will make him understand the special way in which he is destined to serve. The hero of Goethe's great novel, Wilhelm Meister's Travels, is led, by his experiences and reflections, to serve as surgeon to a group of emigrants. Goethe's philosophy about the world and about life also embraces the idea of forgiveness. He is certain that no human being, however he may have sinned, has any reason for despair. The grace of redemption is given to man in the service of mankind. The message of forgiveness, which Goethe wishes to proclaim in Iphigenia, is explained by some words he writes in 1827: "Every human failing may be expiated by pure human virtues." If love is the very essence of spirit, God can only be conceived as the fullness of love. Goethe confesses, "I consider that faith in the love of God is the sole basis on which my salvation rests." Man must put this notion of the world and of life into active practice. Goethe considers as an aberration any slightest impulse that is at bottom contemplative. This view leads him, in Faust, to violate the text in the first verse of the Gospel of John: "In the beginning was the word" (in Greek, logos). Goethe translates it: "In the beginning was action." He never ceases to extol action. "The realm assigned to human reason," he says, "is that of work and action. In activity one runs little risk of going astray." Or again: "Man's salvation lies in devoting himself to the daily toil while combining meditation with it. . . . "Thought and action, action and thought, this is the sum of all wisdom, known from the beginning, practised from the beginning, but not acknowledged by everyone . . ." Und dein Steben sei's in Liebe, Und dein Leben sei die Tat. Let thy search be in affection, And thy living be in deed. It is through activity that a man most easily gives an account of himself. To the question of how a man can best learn to understand himself, Goethe replies, "Try to do your duty and at once you will know what kind of man you are." But what is duty? Goethe replies, "It is what the day demands." It is for us to open our eyes, in order to become aware of our immediate duties and to assume them. In doing so, we become men capable of determining which tasks remain for us to accomplish. Permit Goethe himself to speak: Was jeder Tag will, sollst due erfragen, Was jeder Tag will, wird er sagen; Musst dich an eigenem Tun ergetzen, Was andere tun, das wirst du schätzen, Besonders keinen Menschen hassen Und das übrige Gott überlassen. What every day wishes you must ask. Each day will tell you, this your task. Take pleasure then in what you do; The work of others honor too. Let no man ever make you hate; For all else to God entrust your fate. And again: Dir selbst sei treu und treu den andern. To self be true, and true to others. . . . Let us touch upon Goethe's religion. This is identical with his philosophy of the world and of life, a conception in itself both ethical and religious. In proclaiming and in incarnating the love of God, says Goethe, Jesus does no more than reveal to us what we should ourselves come to know through reflection. For Goethe, true religion is not found in the dogmas about Jesus and his work, but in the religion of love which Jesus proclaims. This is an understanding reached by the religious rationalism of the eighteenth century. Goethe makes it his own. Even as a young student at Leipzig he is devoted to Jesus' religion of love. The following anecdote illustrates this. One morning the young student finds himself in the livingroom of the engraver Stock's home. While the engraver is busy about his art, the teacher of his two young daughters, Dorothy and Marie, is giving them a lesson in religion and has them read aloud from the Book of Esther. Suddenly the young student vehemently reproaches the teacher for making the girls read this story. Taking the Bible himself, he opens it to the Sermon on the Mount and says to Dorothy, "Read this to us, this is the Sermon on the Mount. We will all listen to you." The poor child's emotion prevents her from reading, so Goethe reads the sermon in her place and comments upon it as he reads. In 1773, the youthful Goethe writes (simulating the letter of a preacher to a brother clergyman), "I hold to faith in the divine love -- which, so many years ago for a brief moment in a little corner of the earth, walked about as a man bearing the name of Jesus Christ -- as the foundation on which alone my happiness rests." Thus, love is for Goethe the highest expression of the spirit; he cannot think of God, the epitome of everything spiritual, except as the fulfillment of love. Sometimes, particularly in the years that follow his first sojourn in Italy, Goethe likes to call himself a pagan, but this does not mean that he considers himself irreligious. Instead, it indicates only that he clings to a religion which does not follow the tenets of dogmatic Christianity. He asks teachers of religion to consider it their duty to conduct the faithful more and more away from traditional forms and toward pure religion. His principal complaint about dogmatic Christianity is that it pictures God as being outside of nature instead of within and manifest in it. Goethe does not intend to abandon the idea of God's identity with nature, in favor of Spinoza's notion of Deus sive Natura (God or Nature). He is convinced that only the idea of the immanent God will make it possible to be pious and honest at the same time. It causes him a great deal of pain that Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi, who once shared with him an enthusiasm for Spinoza, renounces the conception of God they had cherished in common. In a book he publishes in 1811, Von den Göttlichen Dingen und Ihrer Offenbarung (Of Things Divine and Their Revelation), Jacobi advocates the idea that nature does not reveal God. After reading this book, Goethe writes (in his 1811 Annals), "With my pure, profound, innate, and tested way of viewing things, which had taught me to see God in nature and nature in God so indissolubly joined that this conception had become the basis of my entire existence, it was inevitable that such a strange, narrow, and superficial declaration should alienate me forever from the noblest of men, whose love I once cherished devotedly." Goethe sets down his own conception of God, as contrasted with Jacobi's in these verses: Was wär' ein Gott, der nur von aussen stiesse, Im Kreis das All am Finger laufen liesse! Ihm ziemt's, die Welt im Innern zu bewegen, Natur in sich, sich in Natur zu hegen, So dass, was in ihm lebt und webt und ist Nie seine Kraft, nie seinen Geist vermisst. What God from outside would propel his world, The universe around his finger twirled! He rightly is the earth's deep-centered motion, Nature and He in mutual devotion, So that what lives and moves and is in Him Will never find His strength and spirit dim. In the next to the last line he refers to the words: "For in Him we live and move and have our being," which, according to the report in the Acts of the Apostles, belongs in the speech given by Paul on the Areopagus at Athens. This speech was provoked by the altar dedicated "to the unknown God" (Acts 17:16-34). The objection that this pantheism seems to exclude the idea of a personal God does not move Goethe. He believes that spirit is personal, in a way that we cannot imagine. He is in complete sympathy with the religious instruction that his son August receives from Herder in preparation for his confirmation. Herder makes the boy see that the natural state of man is one of confusion and conflict between light and darkness, between God and evil, and that the Christian religion sets before him the question of whether he wishes to belong to the darkness, or to the light that came into the world with Jesus. Going on from this, Herder teaches the boy about man's need of help, from which springs the necessity of salvation arising from the love of God. Goethe discusses Christianity with Eckermann on March 11, 1832, a little while before his death: "No matter how far our spiritual culture may continue to progress, no matter how much the natural sciences may grow, becoming ever more profound and more inclusive, no matter how much the human spirit may will to expand, that human spirit will never escape from the majesty and ethical sublimity of Christianity, as it shimmers and shines in the Gospels." He esteems the Reformation and finds in it a very rich meaning. "We are not at all aware," he says, "how grateful we should be to Luther and the Reformation. We have been freed from the fetters of spiritual ignorance; in consequence of our growing culture we have become capable of going back to the source and of comprehending Christianity in its purity." Concerning immortality Goethe confesses, "I am firmly convinced that the spirit is an indestructible being." He leans toward the hypothesis that whatever is indestructible in us can be called to new activity, either in this world or in some other. But he is of the opinion that it does no good to express judgments on things beyond our knowledge, and that the wisest conduct is not to concern ourselves with the future world, but to try above all else to fulfill our mission in this present one. Several times he declares that he can talk only with God Himself about these ultimate questions which man confronts. He sums up his thoughts about the limits of our knowledge in these words: "The greatest happiness of the thinking man comes from having explored that which is explorable and from venerating serenely that which is unexplorable." He energetically protests the presumption of religion in depreciating knowledge acquired by research and reflection. "It would not be worthwhile to reach the age of seventy," he says, "if all the wisdom of the world were but foolishness to God." His world and life view, as well as his religion, may be summed up in these wonderful words: "Quietly a God speaks in our hearts; quietly and clearly he shows us what to seek and what to avoid. . . . "Above all the virtues one thing rises: the ceaseless striving upward, the struggle with ourselves, the insatiable desire to go forward in purity, in wisdom, in goodness, in love." These are the elements in Goethe's philosophy. While he is alive, it does not attract much attention. It is a little shrub growing in the shade of the great systems of Fichte, Schelling, and Hegel. But toward the middle of the nineteenth century these great systems collapse, unable to hold their own against the increasingly flourishing natural sciences. The shrub of Goethe's philosophy remains standing. Freedom from oppressive shadows, it thrives and becomes a true tree. More and more the philosophy of Goethe takes on importance, even though he expounds it only in fragments. It grows because it has nothing to fear from the natural sciences, since it is based on them and is in harmony with them. It represents, then, a philosophy that has a future. It rests on the fact that, since our knowledge of the universe is incomplete, philosophy must be incomplete also. For this reason, Goethe is intent upon establishing, by experience, the fact that man must start with reality. When man remains in constant contact with reality, and never wavers in his fidelity, he can reach convictions, through research and reflection, which will permit him to lead a truly spiritual existence. Goethe thinks he has succeeded. He shares with us the result of his research and meditations about the world and man, as something experienced by him. His words convey profound and practical wisdom about life, and constitute a unique spiritual treasure bequeathed by one man to his fellows. One last question: do the thoughts of Goethe, which he shares with us, benefit by the authority of his personality? What, indeed, is this personality? Those who wish to criticize Goethe can find plenty of material. He has committed faults. His way of life is in many respects strange and disconcerting to us. We do not understand for instance, his behavior toward Christiane Vulpius. They live as man and wife for eighteen months before he legally marries her and gives her, in the eyes of the world, the status to which she is actually entitled. How is it possible for him to prolong a situation which must bring him, and especially her, so many difficulties and so much humiliation? How shall we understand, in general, the spirit of indecision which he displays on more than one occasion? And this lack of naturalness which he also exhibits! When his prince and friend, Karl August, dies, he does not render to him the last honors, which he should have done in any case as the prince's prime minister. Instead, he asks Karl August's son and successor to excuse him from taking part in the funeral ceremonies, so that he may retire to the country to master his grief. He does not even take part in writing the necrology. And why is it that he sometimes affects a certain coldness, although he really feels more cordial than his expression implies? Why does he occasionally permit himself to indulge in sarcasm, in which the spirit of Mephistopheles seems to break through? Let us stop here in this enumeration of his peculiarities. What opinion does Goethe hold of himself? In a 1775 letter, he writes that he possesses "all the contradictions that are possible to human nature." In Poetry and Truth he judges himself and says that his nature is constantly wavering between extravagant gaiety and unpleasant melancholy; these different moods are forever pushing him to one extreme or the other. In a 1780 letter, we find these words: "I am, as always, the embodiment of thoughtful levity and warm frigidity." To Christian Schlosser, the nephew of his good friend Friedrich Christoph Schlosser, the aging Goethe writes in 1813, "Why should I not admit to myself that I belong among those men in whom one may live, but with whom life is not pleasant?" He is neither a harmonious personality nor an ideal one. Yet his contemporaries who know him well eulogize him. Knebel, who lives with him in Weimar, writes to the theologian Lavater at Zurich, "I am well aware that he is not amiable every day; he has an unpleasant side, which I have myself experienced. But, taken all together, he is remarkably fine. Even in his kindness, he is surprising." Schiller, in a letter to the Countess Schimmelmann in 1800, judges him similarly: "It is the notable aptitudes of his mind that attract me to him. If I did not think that he possessed, as a man, the greatest significance of all those that I have come to know personally, I should be content to admire his genius from a distance." From Jung-Stilling, a close friend of Goethe's from Strasbourg days, come these lovely words: "His heart, which was known to but a few, was as great as his intelligence, which everyone knew." Today, because of the mass of information we possess about Goethe, we can see his life spread out before us. (This is not the case with any other distinguished man of the past.) We cannot but think of him as a great, profound, dominating, and -- in spite of all his peculiarities -- congenial personality. We are first impressed by the deep seriousness which characterizes him from childhood on. From adolescence to old age, he is profoundly and seriously concerned with himself; he is determined to master his quick temper, which continually tries to get the upper hand. As early as the Leipzig period, his passionate character and his power to control it are seen side by side. At Wetzlar, in 1772, Kestner draws a detailed and interesting psychological portrait of him, revealing this aspect of his personality. At Weimar, Goethe is bent upon attaining complete mastery over himself. The soul-searching which he confides to his diary at that time bears witness to this, and the diary reveals the wish he then expresses: "May the ideal of purity become ever more clear within me." He is speaking of his own experience when, at the age of thirty-five, he announces in the poem "Secrets": Von der Gewalt, die alle Wesen binder, Befreit der Mensch sich, der sich überwindet. From the great powers that every creature bind The man who conquers self will freedom find. In another poem, he expresses the thoughts of victory over self in the words: Das Opfer, das die Liebe bringt, Es ist das teuerste von allen; Doch wer sein Eigenstes bezwingt, Dem ist das scöhnste Los gefallen. The sacrifice that love doth bring Is precious treasure to enthrall; Yet he, his own self mastering, Will have the happiest fate of all. Through this continuous effort to control himself, his behavior becomes stiff and artificial and may be interpreted as pride. His very large and impressive eyes, and his severe features -- all inherited from his grandmother Textor on the maternal side -- help to give him a deceptively Olympian appearance. But when he realizes he is dealing with persons who have a certain just claim upon his interest, and not with visitors who have come out of mere curiosity, he abandons this Olympian pose and becomes affable. The Austrian poet Grillparzer, who has seen him make this transformation, describes the impression that the aged Goethe made upon him in these words, both charming and true: "He looked half like a king and half like a father." The description of Goethe as "the Olympian who rules the world from his throne," comes from Jean Paul, the satirical writer who stayed at Weimar from 1798 to 1800 and who was out of sympathy with both Schiller and Goethe. An excellent picture of the Goethe who is both reserved and outgoing is drawn by Eckermann in the preface to the third part of his Conversations: "His self-control was great. It was indeed a distinguishing characteristic of his nature. Because of that very attribute, however, he was often -- in many of his writings, as he was also in his spoken word -- restrained and full of consideration. As soon, however, as some daemonic power animated him in moments of happiness, his conversation became impetuous and youthful. At such times he expressed the greatest and the best in his nature." Another fundamental trait of Goethe's character is veracity. On February 22, 1776, he writes to Lavater that he wants to become as true as nature is. In short, he wants to remain absolutely true and sincere, even in his daily intercourse with men, although as a result he is accused of lacking amiability. Because of his sincerity and truthfulness, all intrigue is foreign to him. He feels no stirring of jealousy. All this together constitutes the innate nobility of his character. He has a taste for occasional friendly humor, and displays it. But humor that has become a constant mood, always trying to be comical and indulging in satire, he consdiers a silly and reprehensible way of playing with things. Only a skeptic, he believes, can behave in this way. No man can be honest who is not indeed earnest with life. On the whole, Goethe has an unconquerable repugnance for everything that is in any way grotesque. Harsh and spiteful judgments are not for him. "I see," he once said, "no faults committed, which I might not also have committed." In challenging verses that spring out of deep feeling, he condemns the outlook of the cynic: Der Teufel hol' das Menschengeschlecht! Man möchte rasend werden! Da nehm' ich mir so eifrig vor: Will niemand weiter schen, Will all das Volk Gott und sich selbst Und dem Teufel überlassen! Und kaum seh' ich ein Menschengesicht, So hab' ich's wieder lieb. The devil take the human race! It might well drive one mad! I eagerly begin to think That none would see more clear, The people all, God and themselves To the devil relegate! Yet seldom do I see man's face But liking comes again. This man so deeply in love with the truth is, at the same time, a humble being, not only toward God but also toward other men. All roads are made smooth for me "because I walk humbly," he writes to Herder from Rome on January 31, 1787. Whenever he encounters superior volition and ability, he silences his own self-conceit. He has no other desire then, but to appreciate and to learn. This is his attitude toward the artists with whom he associates in Rome. This is his attitude toward the investigators who help him win new knowledge in the natural sciences. This is his attitude toward Schiller, to whom he submits himself spiritually to an almost incredible degree. And, in general, what humility he displays in his intercourse with men! There is abundant testimony about his kindness. We know of needy persons whose heads are kept above water for long periods of time through his generosity. To one of these protégés who thanks him for his help, Goethe replies (on November 23, 1778), "you are not a burden to me; on the contrary, this is teaching me to economize. I fritter away a good deal of my income that I could spare for those in distress. And do you think that your tears and your blessing are nothing to me?" We know that he places at the disposal of Vogel, his physician, whatever is necessary to assist those in his practice who need help. He often sacrifices time and trouble to render service to those whom circumstances reveal as deserving of his fraternal love. As an administrator, the improvement of living conditions of the people for whom he is responsible is very close to his heart. The need to serve dominates Goethe's life. He never shirks any duty incumbent upon him; he never tries to avoid any responsibility. The smallest duty is performed with the greatest conscientiousness. He always commits himself to the limit of his ability. And all of these qualities are thrown into relief by Goethe's continuous effort to perfect himself, an effort which is rarely seen in other personalities who attract our attention. This is Goethe -- the poet, the sage, the thinker, and the man. There are persons who think of him with gratitude for the ethical and religious wisdom he has given them, so simple and yet so profound. Joyfully, I acknowledge myself to be one among them. Goethe: His Personality and His Work - Albert Schweitzer - 1949 NUMPAGES 20 |

ALBERT SCHWEITZER COLLECTION - STEPHENS COLLEGE

ALBERT SCHWEITZER INSTITUTE AT CHAPMAN UNIVERSITY

ALBERT SCHWEITZER INTERNATIONAL WEBSITE

THE ALBERT SCHWEITZER INSTITUTE

|

|||

|

"Reverence for life comprises the whole ethic of love in its deepest and highest sense. It is the source of constant renewal for the individual and for mankind." Albert Schweitzer |